During the nineteenth century, people got their information either from things that were written on paper (if they knew how to read at all, which was far from guaranteed) or from things they heard from people sharing actual physical space with them. That was it.

And in fact, it was plenty. Many people wrote letters constantly – expecting to hear from friends and relatives weekly, if not more often – and newspapers proliferated like mushrooms after a good rain. There were also magazines and books, of course, not to mention paintings, etchings, and other forms of popular visual media, especially in the latter part of the century, when photography also made its appearance.

But right now I’m going to talk about newspapers. And Abby Jane Wade of Hartford, Connecticut.

Then as now, one of the mainstays of newspaper coverage was crime and criminals, especially if the crime was gruesome, bizarre, or offered the opportunity to mock or demonize the members of disfavored racial, ethnic, or other groups. Abby Jane Wade’s short career as a public figure (1858-1869) hit each of these notes at one time or another.

She was, as far as I can determine, a person who was disadvantaged from very early in her life. In Nancy Hathaway Steenburg’s Children and the Criminal Law in Connecticut, 1635-1855: Changing Perceptions of Childhood (2005), she appears as an example of how the state would sometimes ignore concerns about the well-being of young people, including of young women, and send them to the state prison anyway. Abby Jane Wade (or Abby Jane Wilcox, as she apparently was also known) had been arrested for breaking into a house in the town of East Lyme and stealing a watch and some clothes, and also for stealing a horse. She was sentenced to a total of four years in the state prison despite being a minor (under the age of 21, at that time).

An explanation of the court’s decision lies in the court’s belief, repeated by Steenburg, that Wade was “a transient young woman.” Transient was a more polite word than vagrant, but the implication was same: a person who had no fixed place of abode or employment was inherently suspect and a threat to society.

Did you think our modern attitudes toward unhoused people just sprang out of nowhere?

Linda K. Kerber, in her No Constitutional Right to Be Ladies: Women and the Obligations of Citizenship (1998), offers a partial explanation of the basis of this view: one of the assumed, generally unspoken obligations of citizenship seems to be the obligation not to be a vagrant. This automatically criminalizes anyone who is, or appears to be, unhoused and/or unemployed. As a transient person, Abby Jane Wade was someone who the court “naturally” believed needed to be punished, and her actual criminal acts only added to that need.

Her initial case does not appear to have made any impression on the public. She became famous because of what she did in 1858, after her release from the state prison. The story was, apparently, initially reported in a newspaper called the Hartford Courier, but this text is from the October 26 edition of the Evansville Daily Journal in Ohio:

A girl about twenty-five years of age, by the name of Abby Jane Wade, who had been an inmate of the Connecticut State Prison four years, and was discharged on expiration of sentence a year ago, was found early Sunday morning in the female yard of that prison. Her excuse for this breach of courtesy was her longing for better living than she had been able to obtain since leaving—a strong desire to visit old friends—and again to breath[e] the atmosphere of home. A description of her appearance can be summed up in two words—dirt and rags. After a short confinement she was taken out of the front entrance and advised to leave.

The necessary ingredients for press attention were bizarreness (breaking into a prison!) and mockery – in this case, of a poor person with no resources and no help. Similarly, the Detroit Free Press printed a short version of the story on October 27:

STRANGE ATTACHMENT - Abby Jane Wade, 25 years of age, who was discharged quite recently from the Connecticut State prison, after four years’ imprisonment, was found early last Sunday morning secreted in the enclosure around the prison, and, finding herself discovered, begged piteously to be allowed to remain.

Here, the paper seemed to be emphasizing the weirdness of the event, I think. Not all newspapers have been digitized for searching on Newspapers.com, but if it appeared twice, it seems likely that the story was reported in others as well. Although apparently not in the Hartford Courant, perhaps because they did not want to print it after one of their rivals had scooped them.

I have not learned exactly why she was arrested and imprisoned again, but on May 14, 1860, the warden of the state prison reported that she has escaped. From his notice in the Hartford Courant we have a description of her: “short in stature, round featured, fair complexion, black eyes, 23 years of age. Wore away a linsey dress, with a red stripe.” On May 18, he followed up in the Courant with a $25 reward for her return to the prison.

The reward may have been prompted by something reported in the Hartford Weekly Times on the same day: That she had slipped back into the prison and stolen some food. As the paper reported it:

WADING OUT AND WADING IN: Abby Jane Wade, who escaped from State Prison the other day, has since returned merely for a call, and is gone again. Night before last she scaled the yard wall by the help of a tree, and provided herself with provision from the kitchen, The only way the fact was ascertained was that she left a piece of her dress in her haste. She did not disturb any one, as the hour was late, and it was somewhat inconvenient for her to call earlier. Gen. Welles, of Wethersfield, found that one of his cows had been milked the same day, so that the inference is that Abby Jane luxuriated, at a late supper, on bread and milk. Very likely the time is not distant when she will make a longer visit to Mr. Webster, of the prison, and his family.

Here again the story is treated as humorous: describing her supposed entrance as if it were a social call. This time, perhaps the security arrangements of the prison were the target of the joke as much as the desperate young woman.

On May 22, “Miss Abby Jane Wade” was still at large, and the HartfordCourant finally reported on the fact. I strongly suspect that the paper’s use of “Miss” was intended to be ironic. It mentioned her theft of food from the prison, and went on to add a new anecdote:

This is not the first time that Abby Jane has fled from the face of man. A short time ago she lived with a family in this city. One morning, Abby Jane and a gold watch, belonging to the mistress of the house, were individually and collectively missing. All search for her was fruitless. A week afterwards, the lady of the house, in going down cellar one evening, was startled to see a hand resting on the stairs. She did not know who might own it, but she captured it and gave the alarm. As soon as help arrived, the person who was attached to the hand was drawn out from under the stairs. It was Abby Jane. She had lived a week under the floor of a woodhouse, reaching her nest by removing some of the stones which walled the cellar. At night she came out and helped herself to rations, and was upon a trip for the benefit of her commissary department when she was captured. Abby Jane very likely regained her liberty through a drain, if such an institution leads from the prison to the outer world; though it is not impossible that she yet remains within its walls.

Here again, we have a strange and unusual situation, written about with humor by the newspaper. What is not mentioned in the piece is whether the watch was found, and whether Wade was prosecuted for stealing it. Did she go into hiding because she feared being blamed for the loss of the watch? If she had stolen it, and been able to sell it, surely she would have had some money to get food. The story also does not say whether she was a servant in the house or a charity case; but I think that if it was the latter, then it would have been mentioned as another point of drama. A live-in servant was not unusual for the time and her status as such might have seemed obvious.

On the same day, The Louisville Daily Journal (in Kentucky) revisited the breaking-back-into-prison story in a short paragraph, adding that Wade had been returned to prison for stealing $500 from a Mr. Kennedy in the town of East Hartford. This piece seemed to play on the weirdness of it all, rather than looking for opportunities to mock the subject of it. On May 25, The Bridgton [ME] Reporter reprinted an item from the Hartford Press dated May 15 that brought readers up to date on her escapades, stating that she scaled the prison wall on Monday morning, “while the matron was giving directions to another prisoner about the breakfast.”

On June 6, the Hartford Courant was able to report that Wade had been captured, in a relatively lengthy article full of ironic mockery, in which the writer gave the impression of reporting on a peculiar species of animal and its habits. The piece is too long to quote in full, but here are some excerpts to show you what I mean:

ABBY JANE WADE.—This distinguished lady is again the subject of a news item. It will be recollected that she left her quarters at the State Prison a few weeks since, in a mysterious and ungrateful manner. She was there supported, free of expense, and no doubt furnished with the best the prison affords—well clothed, well fed, and well housed—accommodations vastly superior to her common lot.—Still, she yearned for the flesh pots of Egypt, and left. There is no accounting for tastes, and Abby Jane’s in particular … Abby Jane has a peculiar propensity for burrowing in the day time, and rambling about at night. While others take to a habitation and bed, she (Abby Jane) takes to barns, cellars and underground places for repose … reveling in filth and dirt would seem to be her delight; yet when cleaned up and properly dressed she talks well and appears like a likely young woman of about 20. …

Monday morning a careful and final search was made, when Abby Jane was found snugly stowed away in an old box under said barn [on a farm near the prison]. She was introduced to the light of day and marched back to her old quarters. She was dirty and ragged—that is, what there was left to make rags of. Her dress was gone and her whole covering was very scanty.

As in the rest of the news coverage, nowhere does this article suggest that Abby Jane Wade was a fellow human being whose circumstances should inspire sympathy, or at least regret, over whatever led her to behave like this.

Only a few months later, on August 10, the Hartford Courant reported that “Miss Abby Jane Wade and Miss Villetta Fairclough,” who had escaped from the State Prison on Tuesday night, had been given a meal (reportedly out of charity) by a man in Bristol, and repaid him by stealing his horse and wagon. A deputy sheriff pursued them and arrested them in Wolcott.

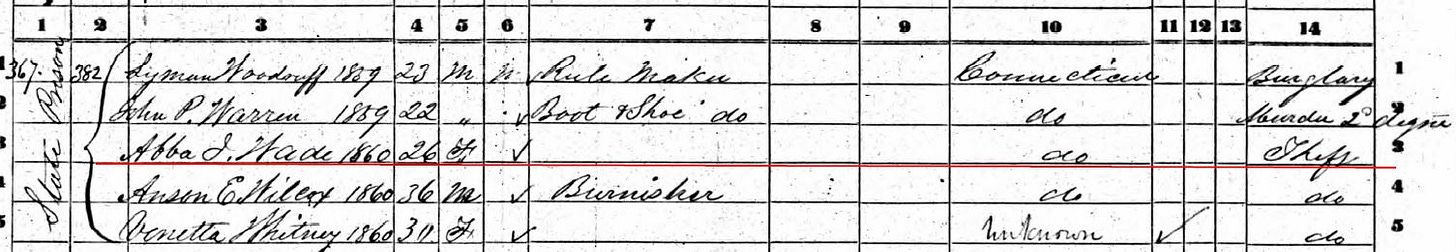

A Hartford Courant article from May 1860 reported that James Fairclough and Vinetta Fairclough were given two years and six months at the state prison for theft, with no ironic or humorous commentary. In July, the federal census marshal arrived at the state prison and counted James Fairclough (age 25, born in Connecticut, imprisoned for theft) and Abba J. Wade (age 26, born in Connecticut, imprisoned for theft). There was no Villetta Fairclough, but there was a Venetta Whitney (age 30, birthplace unknown, imprisoned for theft). Only Wade was notorious enough to appear more than once in the newspaper.

She remained out of sight of the available sources, however, until June 14, 1864, when the Hartford Courant reported that

An old thief and State prison bird made her appearance in charge of an officer at the police station, last evening. She was no less a personage than Abby Jane Wade. Her ruling passion had led her to steal a dress, and, as she has started right, she will probably reach Wethersfield again eventually.

Wethersfield being the location of the state prison. When she appeared in court on June 15 (as reported by the Hartford Courant on the 16th), however, the victim did not appear, and she was released on her own recognizance. The reporter apparently spoke to her, with the following results:

The dress, she says, she never stole, but when asked why she burnt it up, replied that she was afraid she might be accused of stealing it, “and I’d rather burn up every dress I’ve got in the world than to be accused of stealing them, for that ain’t my way of doing things,” said she. This remark is considered rather cool for a recent inmate of the State prison, whose life has been devoted to thieving. If she leaves the city before next Wednesday [her next court appearance], the city will be the gainer.

He also noted that the chief of police had had her picture taken to add to his “rogues’ gallery.”

But the other thing that this report revealed is that in 1864, Abby Jane Wade had friends. There were no references to hiding in holes or dressing in rags in this article or in later ones, which I think can be attributed to having friends—perhaps ones she had met in jail. But they were not the kind of friends that the dominant society of the time considered appropriate for her, with her “fair complexion.” The paper noted,

Abby had a host of colored sympathizers around her, most of whom are habitues of the low haunts that thrive in Charles street, and with whom she is in the habit of associating.

The reporter did not need to say that this was, in his view, another stroke against her character; his readers knew that very well.

On July 1, the Hartford Courant reported that Wade failed to show up for the continued hearing, and she was not found until she was arrested in the town of Hebron, on the 27th, for stealing a horse; she gave her name as Abby Jane Wilson, pled guilty, and was jailed there. “She evidently likes Wethersfield,” the reporter noted dryly, “and is figuring to reside there again.”

On March 14, 1865, the Hartford Courant briefly revisited the police departments rogues’ gallery, naming Abby Jane Wade, “now in the Tolland county jail for stealing a horse,” as one of the “sitters.” On December 4, the same paper reported the minor headline “Abby Jane Wade Heard From,” noting that “it was generally supposed she was in the State prison or county jail as usual, but it seems she has lately been enjoying a surprise party—freedom from arrest—on Commerce street.” The notice came because a Black man had stolen a watch from her and been arrested – and “The fact is worthy of mention only to show an extraordinary incident in Abby’s life—that for once she appears as a loser by a theft operation. It isn’t her style, by a long shot.” Amused contempt was still the order of the day in this news coverage, even where she was the victim.

By November of 1867, Wade was doing well enough for herself that she had a house on Charles Street. (Presumably it was rented, and in any case the Hartford land record index shows no land purchases by her.) She played a minor role in a horrific crime: a shopkeeper was killed in the course of a robbery, apparently by accident, and a white Englishman and two Black men were arrested for it. The Black men, Alexander Henry and Samuel Lang (who was soon cleared of involvement) were found and arrested at Abby Jane Wade’s house. This matter was treated very seriously, probably because a man had died.

On February 7, 1868, the opportunity for contemptuous humor at the expense of both Wade and Black people had arisen, and the Hartford Courant reported as follows:

Chicken Raiders Gobbled

The Hartford police on Thursday arrested in the mansion of the celebrated Abby Jane Wade, on Charles street, a “small but select” party of some dozen or more negroes, who were about to enjoy a feast of “chicken doin’s,” supposed to be the result of a raid the previous night into East Hartford, which devastated the roosts of several persons there. The cheerful assemblage was at once transferred to the police station, to be in readiness to attend the levee of the police judge this morning.

It is, needless to say, unlikely that a poor woman like Wade lived in a “mansion.” The remainder is a specimen of the kind of racist humor that portrayed Black people as foolish clowns. The outcome of these arrests is not known.

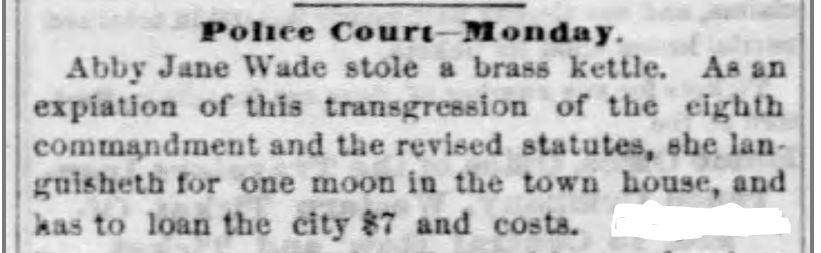

The later reports from 1868 indicate that overall, Wade had become less interesting to the Hartford Courant. Her arrest on a charge of stealing 50 pounds of hay was reported factually on April 27, and so was May 9 report of her arrest for allegedly stealing a brass kettle. The newspaper attempted to revive the joke in its reporting on May 12:

Abby Jane Wade stole a brass kettle. As an expiation of this transgression of the eighth commandment and the revised statutes, she languisheth for one moon in the town house, and has to loan the city $7 and costs.

But a decade had passed since the incident of a young woman trying to return to prison caught the attention of the press, and if Wade was 26 years old in 1860, by 1868 she was 34 and had not done anything really outrageous for many years. The joke was old. The last mention of her that I have found in newspaper searches is from June 5, 1869, when a man was “arraigned for creating a disturbance at the ‘Red, White and Blue,’ kept by Abby Jane Wade.”

Although her name did not turn up otherwise, I did discover that this Red, White and Blue place—presumably a saloon—was also famous in its own way. On July 16, 1869, the Hartford Courant reported that “The notorious ‘Red, White and Blue’ house on Commerce street came near being destroyed by fire at about 3 o’clock yesterday morning. … Had it burned to the ground, the loss would have occasioned little regret in that neighborhood.”

And that is the end of the story.

Really. I have no idea where in Connecticut Abby Jane Wade was born, or to whom. I have not been able to find out whether she died or just became too boring to be featured in the paper. Perhaps managing a saloon provided enough money for her to avoid any more stealing. Neither she nor the Red, White and Blue were the type to be listed in city directories. Perhaps she married and changed her name, but I have not been able to find any evidence of that, either.

Abby Jane Wade became briefly famous for being young, desperate, and poor as dirt. Her society and its legal system considered her to be a threat to the proper order of things, to be disciplined by prison and public contempt. Her circumstances and actions were considered newspaper fodder because making fun of such people was entirely normal. Once she stopped being “interesting”—nothing more can be found about her.

I am, honestly, not at all sure that we have become any better than this.

What I’m Reading

As I mentioned above, I’m reading Linda K. Kerber’s No Constitutional Right to Be Ladies: Women and the Obligations of Citizenship (1998), which I picked up nearly at random at Nutmeg Books in Torrington.

As I mentioned on Twitter earlier this month, this book (which I haven’t even finished!) is one of two things I’ve read lately that really slapped me upside the head and said “You’ve been thinking about government all wrong!” The other is an essay critiquing the entire concept of the Supreme Court being the final arbiter of what is constitutional, which I am horrified to discover that I cannot find, even though I downloaded a copy. Drat.