The Library of Benjamin Douglas, Part 1

A while back, I ran across the item-level inventory of Benjamin Douglas’s library in his 1775 probate record. It included no fewer than 60 titles, many of them multi-volume, and that is an impressive number of books. The inventory also included his wife Elizabeth’s books, because in 1775 a married woman’s property was legally her husband’s property, and that was another 12 titles, some of which were also multi-volume. They each also owned pamphlets that were not separately listed (3 for her, and 36 for him).

So who was this guy who owned so many books, and whose wife also was educated enough to have her own library? He is not famous, but frankly that is likely because he was only 37 years old when he died. The library tells us that he was a lawyer, because more than half of his books were law and law-related works. Guessing that he was a Yale graduate (the next guess would be Harvard), I looked him up in Dexter’s Biographical Sketches of the Graduates of Yale and there he was in Volume II. He was born in Plainfield, August 29, 1739, graduated from Yale in 1760, and joined the bar in New Haven in 1762, where he also resided, becoming King’s Attorney for New Haven County before his death.

His probate inventory shows that he was a slaveholder, keeping two people (a 20-year-old man and a 13-year-old girl, called Harry and Candice) in then-legal bondage. This fact did not, alas, prevent his contemporaries from believing that he was a delightful and universally-loved person. Would he have become a revolutionary? Would the concept of “liberty” have percolated through his mind well enough to imagine liberty for enslaved people? He missed his chance to show us, but his library does offer some hints.

In fact, I would not be interested in Benjamin Douglas outside of my research project if it weren’t for his library. Outside of the most wealthy and prominent families, the fate of most private libraries at the death of their owner is to be broken up and sold. Worse, probate inventories most often just refer to a “lot of books” and their collective value. Here, we have an itemized list. We can look through them to see what the books’ owners were reading – what food they were giving their minds.

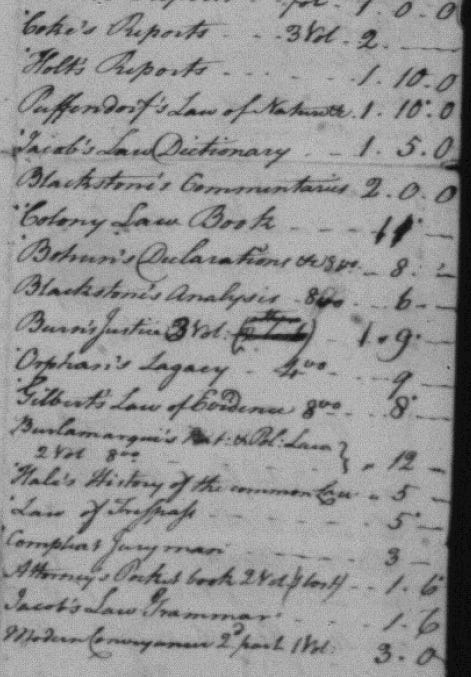

Now, 32 of Benjamin’s books were law books, and most of those were basic reference texts about case law, specific legal theories, etc. The fact that he owned “Jacob’s Law Dictionary” only tells us that he was a lawyer. But there were two books that the men making the inventory lumped in with the law books, probably because they had the word “law” in their titles, that were not really law books. They were “Puffendorf’s Law of Nature &c” and “Burlamarqi’s Nat: & Pol: Law” in two volumes (the latter in octavo format, meaning they were printed in relatively small volumes).

These were actually works of Enlightenment philosophy.

“Puffendorf” was Samuel Freiherr von Pufendorf (1632-1694), whose work was originally written in Latin and called De Jure Naturae Et Gentium Libri Octo, or On the Law of Nature and of Nations in English. Published in 1673, it was translated and reissued many times; this edition [https://archive.org/details/oflawofnaturenat00pufe/page/n6/mode/1up], from 1729, was probably pretty close.

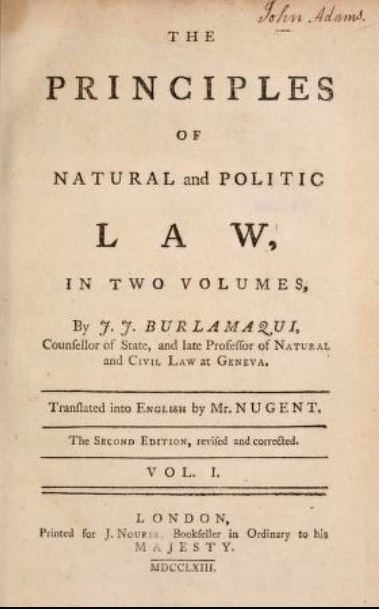

“Burlamarqui” was Jean-Jacques Burlamaqui (1694-1748), whose works Principles du Droit Naturel (1747) and Principes du Droit Politique (1751) were later translated and published as The Principles of Natural and Political Law, again in many editions. This 1763 edition [https://archive.org/details/principlesofnatu01burl] could have been the one that Benjamin Douglas had.

Natural law was a project of the Enlightenment, was intended to provide a rational, organized alternative to scriptural authority for the laws and rules of society. It included the concept of natural rights, and sought to use human reason to develop systems of law, morality, and ethics – with the same ultimate goal as religion, namely to create a just and orderly society. Unfortunately it drew on society as it existed at the time and tended to assume that the common denominators among existing systems represented “natural” laws. Thus, such Enlightenment thinkers quite often developed “rational” reasons for the existence of slavery, for the subjugation of women, for corporal punishment, and so forth. I’ve been disappointed in the Enlightenment since I realized that in many ways, its thinkers substituted “nature” for “God” instead of really taking human responsibility for human behaviors and systems.

But I digress. What these two books tell us about Benjamin Douglas is that he had received a mainstream eighteenth-century education in law and philosophy. Concepts of natural law were part of the ordinary furnishings of an educated man. In the year after his death, the Declaration of Independence would include in its first sentence the phrase “the laws of nature and of nature’s God.” Both the pro- and anti-independence sides of the Revolutionary argument used the same set of concepts, only reaching different conclusions from them.

I don’t recommend trying to actually read these two books – scanning their tables of contents will tell you a lot about them. It’s dense material even without the convoluted syntax that the writers of their period tended to use. Some of the other books he owned, which I’ll talk about in some later newsletter, will be a little easier on the brain.

What I’ve Been Reading

Meghan K. Winchell, Good Girls, Good Food, Good Fun: The Story of USO Hostesses During World War II (2008). An interesting sociocultural history of a phenomenon that was, when you really think about it, pretty darn weird and quixotic.

Kevin M. Levin, Searching for Black Confederates: The Civil War’s Most Persistent Myth (2019). This won’t be to everyone’s taste, but I appreciated Levin’s highly detailed review of the evidence and how it’s been misused to pretend that there were bunches of Black Confederate soldiers.