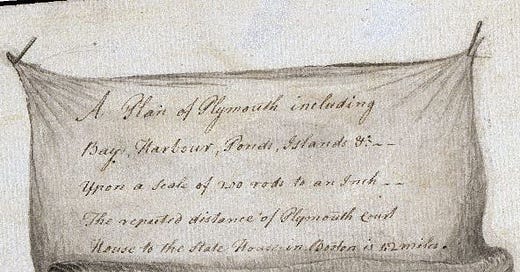

While looking over a map from approximately 1794, I noticed the following annotation off the coast of Plymouth, Massachusetts. Around a drawing of a two-masted sailing ship, it says “Magee’s Shipwreck December 26 1778.”

Intrigued – why commemorate an event that occurred some 16 years before the map was made? – I indulged in a little quick Googling. It was, in fact, a deeply tragic event: the American privateer General Arnold, captained by James Magee, ran aground on White Flat during a blizzard, no more than a mile off the shore, and over 70 of its men froze to death even while Plymouth townsmen tried in vain to rescue them.

In a survey of other historic maps of Plymouth, I found that an unnamed “wreck” was noted in an 1853 U. S. Coast Survey map, and on an 1857 map of Plymouth County. Whether this was the wreck of the General Arnold is uncertain, for reasons discussed below.

What is more certain is that the event reverberated in local memory for many years. The map drawn in the 1790s, which was almost certainly done by a local man, is the first example. The second is a history of the town of Plymouth published in 1832, which was 54 years after the event. The author, James Thacher (who was a medical doctor as well as a general scholar), devoted a full two pages to the story of the shipwreck. I suspect, however, that it was drawn from, if not actually copied from, an earlier book about the wreck that was written by a survivor, Barnabas Downs, Jr., and published in 1786. In the style of early books (which often received no advertising other than the listing of their title), it was called A Brief and Remarkable Narrative of the Life and Extreme Sufferings of Barnabas Downs, Jun.: Who Was Among the Number of Those Who Escaped Death on Board the Privateer Brig Arnold, James Magee, Commander, which Was Cast Away Near Plymouth-Harbour, in a Most Terrible Snow-storm, December 26, 1778, When More than Sixty Persons Were Frozen to Death: Containing Also a Particular Account of Said Shipwreck. I have not been able to examine this book myself, as it is only available in print or via Evans Early American Imprints (to which I have no access). It is the only first-person account of the wreck that I have been able to identify, however, which makes it the most likely source of Thacher’s details. I think that Downs was probably the source used by Edward Rowe Snow in Storms and Shipwrecks of New England, which also recounts the story, though I am sorry to say that prior experience with Snow’s work suggests that he is not always a reliable source. I use both Thacher and Snow, however, as sources for the following description of the disaster.

As I write this, an overnight December nor’easter is moving into New England. We had days of warning that it was coming, and we have central heating and a moderate faith that the electricity will stay on. In 1778, the only warning of an oncoming storm would have been the clouding over of the sky and the wind picking up. Perhaps someone’s bad knee might have registered the change in air pressure, which may also have been noted by the owner of one of the relatively rare barometers. When the General Arnold left Boston on December 24, however, there would have been no way for its captain and crew to know that it was sailing into a deadly storm.

The General Arnold was a brig or brigantine, a two-masted wooden sailing ship. I am not sure of its exact size, but it was probably about 100 feet long, or perhaps six and a half car lengths. The crew reportedly numbered 105 men and boys. (For comparison’s sake, the famous early twentieth-century ship Titanic was a little under 900 feet long.) As a licensed privateer, headed out for what they called a “cruise,” the General Arnold also carried 20 cannons, and some of the men aboard were “marines.” And yes, the ship was probably named after General Benedict Arnold, who in 1778 had not yet displayed his treachery.

By Friday, the 25th of December, Captain Magee realized that a storm was coming on and sailed for Plymouth Harbor. Arriving after dark, he had no choice but to anchor off the coast. Plymouth Harbor is dangerous, and he needed a pilot to come aboard and guide the ship safely in, which could not happen at night. But none of the precautions he took to reduce the ship’s profile in the wind and shift weight to its hold (by moving most of the cannons there) were enough. The waves and freezing wind grew so strong that the ship’s anchor began dragging along the ocean floor instead of holding the ship in place. The direction it was pushed was toward the shore. Before long, the ship ran aground in an area of shallows called White Flat.

Daylight on Saturday found the General Arnold deeply embedded in the sand, lashed by wind and waves that threatened to break up the ship entirely. It can be difficult to imagine the power of waves: most of us only see and play in the smaller ones, and many others have only seen them on a screen. But water is heavy – just fill up a bucket with water and lift it a few times. Now imagine a mass of water the size of a tractor-trailer hitting you. It doesn’t have to be moving fast, because it out-masses you by many orders of magnitude. Ships, even now, are not designed to stand up to waves, they’re designed to float atop them. Captain Magee’s ship was in deadly danger.

Also, once the waves damaged the ship enough, as well as starting to sweep over the deck, everyone on board was soaked to the skin. Cold and wet is very dangerous, and during this day members of the crew began to succumb to hypothermia. The snowstorm was so heavy that ship and shore were invisible to one another throughout the day. Fortunately for the ship, the tide went out during the afternoon, drawing away enough water that the waves no longer threatened its integrity. Then, as New Englanders can report often happens after a big snowstorm, the temperature began to drop, freezing many more sailors to death.

Dawn on Sunday the 27th brought lower, but still severe, waves and the returning tide. The cold was strong enough to freeze the more placid stretches of water. The General Arnold’s men could see a schooner frozen into the ice not far off. Three men took a small ship’s boat across the open water, then scrambled across the ice to the other ship, and never returned nor sent the boat back to attempt a rescue of the others. The remaining crew were doomed to endure another day and night of bitter cold.

This is not to say that their plight was unnoticed - with the snowstorm over, people ashore had seen the General Arnold and begun attempts to reach it. But where the sea was not frozen, it heaved with massive chunks of ice and still-strong waves, far too unsafe for their small boats. Instead, they began building a rough causeway of wood across the more solid ice. It was slow work, carried out while the sons and grandsons of sailors could hear the stranded men shouting and screaming for help, and still far from complete at nightfall. They started work as soon as it was light again the next day, Monday. By noon, they finally reached the stranded ship and found 70 of the original 105 men dead, many of them frozen solid as they had died.

It was, unquestionably, a traumatic event for both the victims and the rescuers. To think of the laying out of all these bodies at the county courthouse must bring to mind other grim scenes of mass accidental death, like the sinking of the Titanic or the mid-twentieth-century circus fire in Hartford, Connecticut. A reported sixty of the dead had to be buried in a mass grave in Plymouth, and a few were buried there in individual graves, while other bodies, and the living, were gradually returned to their homes. Captain Magee survived and went on to less disastrous privateering cruises, and then to prosper in the China trade until his death in 1801. He was buried in Plymouth. Snow cites Samuel Eliot Morison (Maritime History of Massachusetts) for the information that he used to hold Christmas parties for the families of his shipmates. The mass grave of the sailors was not marked until 1862, when a wealthy stranger heard the story and paid for an obelisk to be set up there.

It seems likely that the tragedy continued to be remembered locally, at least, though later maps and other nineteenth-century histories do not mention it. I have not been able to review many modern histories of the town (and there are a lot of them that focus on the Pilgrims and Plymouth Colony, and nothing later … even though the separate colony ceased to exist in 1691), so I don’t know how often it came up in the twentieth century before the 1970s.

One thing that happened in the 1970s, though, was that the remains of a wooden ship emerged from the sand and was claimed to be the General Arnold. The discovery set off a four-way court battle over salvage rights, from which the Pilgrim Society withdrew in 1977 because its ongoing research had concluded that the General Arnold had been re-floated almost immediately and sailed away. As William R. Cash, a Boston Globe journalist, reported, others continued to believe the ship was the General Arnold. The argument over whether it was this ship continued through at least 1986, when journalist Maryann Mrowca reported on an effort to excavate another part of the ship and prove its identity. In the absence of articles about the triumphant presentation of that proof, I have to suspect that it was not found.

Is it likely that the ship was re-floated after its 1778 sinking? Yes. Ships and their equipment – especially including the cannons! – were extremely valuable during the war. If it did not actually break up, the General Arnold could have been claimed by its owners and repaired for return to service. It could have become one of many ships that vanished without fanfare during the era before radio, and it may have been renamed after the general’s treachery was revealed in late 1780. I’m inclined, in fact, to believe that the Pilgrim Society’s research found evidence to one or both effects.

Two books about the wreck and the mystery have been published by small Massachusetts presses (or possibly self-published): Bowley and Johnson, The Wreck of the General Arnold: The Story of a Disputed Revolutionary War Privateer Wrecked on the Flats of Plymouth Harbor and Its Effect on the Men Vying to Own Her (1995) and Cavallaro et al., Solved: The Mystery of the General Arnold (2007). There may be copies in Plymouth, but I haven’t been able to visit there to find out.

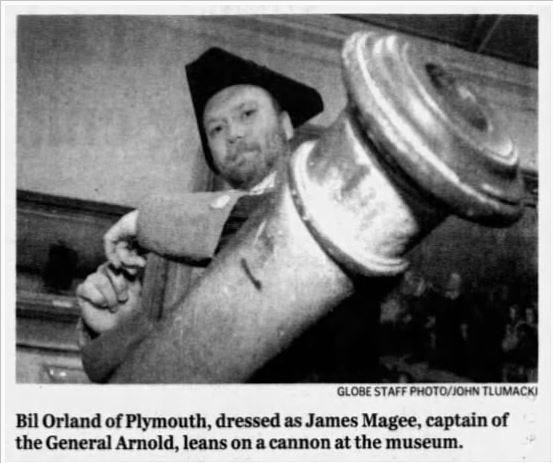

The cemetery monument, Downs’s memoir, the 1794 map, marine archaeology, and several histories also are not the only way the tragedy has been remembered. This newer remembering did not start until the early twenty-first century, however. In 2008, two of the co-authors of Solved spearheaded an effort to identify and memorialize the sailors who died and were buried in the mass grave. Also during these years, the Shirley-Eustis house in Roxbury, once owned and renovated by Captain Magee, began holding public holiday parties hosted by Magee impersonators; announcements in The Boston Globe highlighted his Irish origins and sometimes the shipwreck. The Pilgrim Hall Museum also added “Captain Magee” and his parties to its St. Patrick’s Day roster, and newspaper articles gave the details of the shipwreck (see the photograph below).

Marble and granite memorials are one thing. They’re very traditional. I wonder, though, are these holiday parties, created to help support historic sites, an adequate or appropriate way to keep alive the memory of the terror and grief of the tragedy of 1778? Or is it just the best way, given the ever-growing number of things to be remembered and the near-unimaginable distance between those days and the present?

Bibliography

Campbell, Robert and Vanderwarker, Peter. “Cityscapes, History Lives Here: The Shirley-Eustis House Gets a New Lease on Life.” Boston Globe, Sunday October 27, 1985, p. 427. Accessed via Newspapers.com.

Cash, William B. “Salvagers Vie for Sunken Ship.” Boston Globe, Aug. 27, 1977, Pg. 7. Accessed via Newspapers.com.

Downs, Barnabas, Jr. A Brief and Remarkable Narrative of the Life and Extreme Sufferings of Barnabas Downs, Jun.: Who Was Among the Number of Those Who Escaped Death on Board the Privateer Brig Arnold, James Magee, Commander, which Was Cast Away Near Plymouth-Harbour, in a Most Terrible Snow-storm, December 26, 1778, When More than Sixty Persons Were Frozen to Death: Containing Also a Particular Account of Said Shipwreck. Boston: E. Russell, for the Author, 1786; repr. ed. Yarmouthport, MA: Parnassuss Imprints, 1972.

Knox, Robert. “A 1790s St. Patrick’s Day Party at Museum.” The Boston Globe, Thursday, March 14, 2002, p. 190. Accessed via Newspapers.com.

Morison, Samuel Eliot. The Maritime History of Massachusetts, 1783-1860. Boston: Riverside Press, 1941; Northeastern Classics edition, Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1979.

Plymouth, Town of. “A Plan of Plymouth Including Bays, Harbour, Ponds, Islands, &c.” Maps & Plans No. 1240 (Boston: Massachusetts State Archives, ca. 1794).

Mrowca, Maryann. “British Divers Help Recover Shipwrecked American Revolutionary War Brig.” Associated Press, August 4, 1986. https://apnews.com/article/bf1cf478d11e951f171c4b6a81d93977.

Snow, Edward Rowe. Storms and Shipwrecks of New England. Boston: Yankee Publishing Company, 1943, 1944, and 1946; reprint edition, Carlisle, MA: Commonwealth Editions, 2003.

Thacher, James. History of the Town of Plymouth; From Its First Settlement in 1620, to The Year 1832 (Boston: Marsh, Capen & Lyon, 1832), pp. 216-218.

United States Coast Survey. “Plymouth Harbor and Vicinity.” Sheet T-455. Washington, DC: United States Coast Survey, 1853.

Walling, Henry F. “Map of the County of Plymouth Massachusetts.” Boston and New York: D. R. Smith & Co., 1857.

Wilcox, Emily. “Naming the General Arnold’s Lost Sailors.” The Boston Globe, Thursday, August 21, 2008, pp. 9, 12. Accessed via Newspapers.com.

Wullf, June W. “Family Datebook.” The Boston Globe, Saturday, December 6, 2003, p. 28. Accessed via Newspapers.com.